BLADE RUNNER 2049

Theology of the Body, Human and Replicant

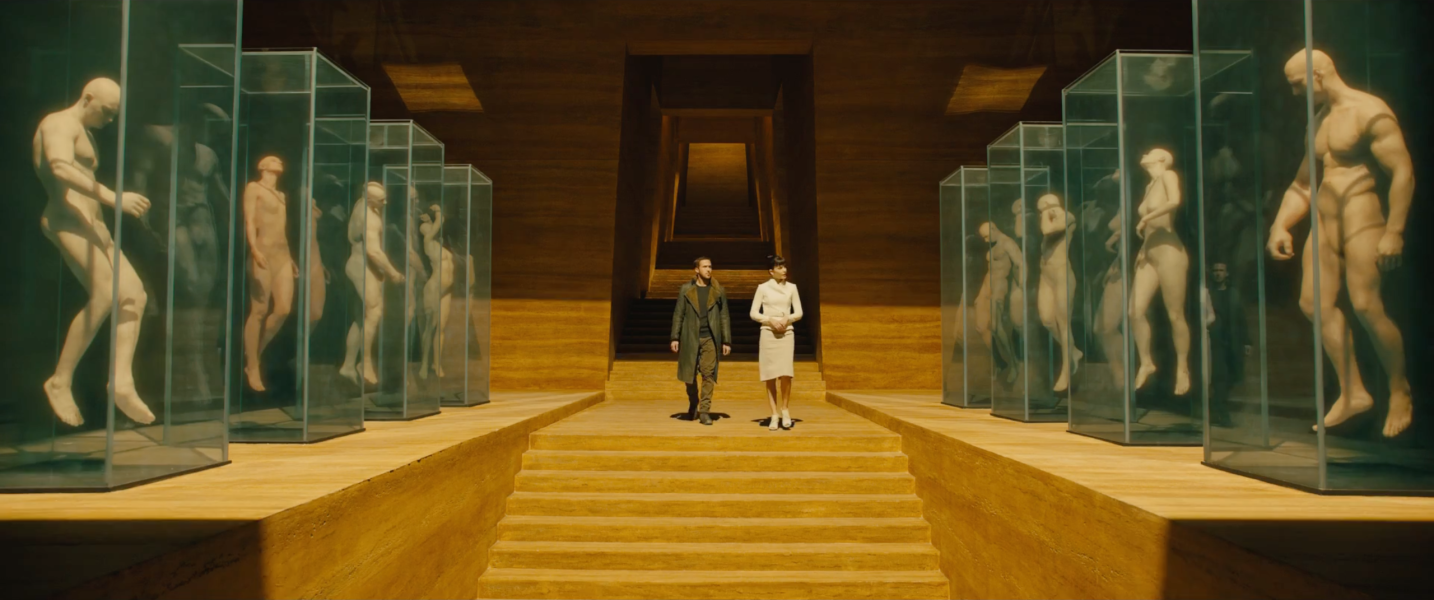

Blade Runner 2049 is a true spectacle. The world provided by the movie is both expansive and detailed, both uncaringly chaotic and deeply personal. Blade Runner 2049 has much to teach us.

From the outset it must be known that for all possible value one may find in the film, there are quite a number of scenes explicit both in sexuality and in violence. Take what caution you will.

Having only seen the movie once, the below plot analysis is not exhaustive, and may not be entirely in order. Please leave a comment if you have suggestions regarding the article.

!! If you have not seen the movie and plan to do so, you should not read this review !!

!!! The content below contains many SPOILERS and now you have been warned !!!

!!! The content below contains many SPOILERS and now you have been warned !!!

The movie focuses on K, an officer working for LAPD as a Blade Runner.

While themes of what it means to be human pervade the first film, those themes were heightened all the more in this sequel, which kept much of the heart of the original intact. The degree to which human embodiment and sexuality are not only crucial to the plot, but also are held up as sacred, was far beyond what expectations might have been held.

PLOT:

A search of the area surrounding the replicant's home leads to the discovery of Rachel's remains, which had long been kept hidden, but not forgotten.

We soon realize that Rachel had given birth to a child, something not considered possible for replicants. Immediately, K is tasked with destroying all evidence of this child because the revelation that humans and replicants can produce such a child would undermine the "wall" separating the two kinds, bringing about the total collapse of human society's colonization of the stars.

Officer K is not the only one looking for the child, however. Niander Wallace, the new owner of a revived Tyrell Corporation, also wants the child, in order to perfect the production of replicants by making them capable of reproducing. Production costs are, after all, bad for the bottom line.

But Niander is not a greedy tycoon, and he talks about his vision for building a great civilization among the stars, which he believes can only be accomplished in the way he believes all great civilizations have been built through history; on the backs of a slave class. He is captivated by both his vision for humanity and of his own godlike role in this achievement, for which he believes terrible means are justified.

Niander's despair over his lack of power over life manifests in a need to exert control over death, shown brutally in a scene in which a new, though sterile, female replicant is examined, kissed, and summarily killed. Not only is this need for control over death what motivates his cold and surely expensive act, but in killing her by cutting open her belly, Niander acts in hatred of the barrenness he cannot help but create. He is able to create "children" for himself, but not yet in his image, with their own power to create life.

As K begins his search, he wrestles with the growing possibility that he may be the child he is looking for, and that his false memories may indeed be real. This suspicion is only fanned by his virtual companion, Joi. There are many aspects that may be worth discussing about the relationship K and Joi have, but one striking scene is when Joi is given a sort of partial body, allowing her to travel with K and to stand out in the rain, herself. Even having this greater degree of corporeality, Joi finds she wishes to be real in a way she cannot be for K, and we have the scene in which she projects herself onto the prostitute in order to be with K like a real girl.

The investigation takes K out to an orphanage, later revealed to be the setting of the memory of his wooden horse. Luv, the replicant assistant to Niander, protects K from above, like "the best angel", for her own desire to follow his investigation to the child.

After being told that the horse must have come from Las Vegas (which has been destroyed and left barren from the radiation of a replicant terrorist bombing), K sets out to find what awaits him. There he meets Deckard, living alone, and confronts him about the child. Before much conversation has been had, Luv and her forces attack, effectively killing Joi, taking Deckard back to Niander for interrogation, and leaving K to die.

Instead, K is picked up by the prostitute, who has tracked his location, and is accompanied by an apparent gang of replicant revolutionaries. The leader of this movement reveals that he is not, in fact, the child, but rather a decoy. His involvement in the investigation, while not a complete coincidence, was not intended to take him this far. She tells him that he must protect the true child, the girl who makes the memories given to the replicants, with his life, and if necessary, by taking the life of Deckard, as well.

Deckard has been led to Niander, who tells him that Rachel and he were programmed, by love or by mathematical equations, to fulfill the desire of Tyrell to prove whether he had solved the problem of replicant reproduction. Deckard rejects a new model of Rachel which is presented to him, noting that they have not matched the color of her eyes. Again we are shown how expendable Niander finds his children to be. Having proven uncooperative, Deckard is taken to be brought off-planet to be tortured into revealing what he knows about the child.

While heading to the launch site, K intercepts and shoots down the transport, battling Luv outright to ensure Deckard is not coerced into giving up his daughter. After accepting mortal injury as a necessary sacrifice, he drowns Luv and saves Deckard. His victory is bittersweet, given his new appreciation for the value of life and his humble role in it, and when Deckard says he nearly drowned while Luv and K were fighting, K tersely remarks that Deckard did drown out there. In saying this, K makes clear that Deckard will be considered dead, and now can live without fear of being hunted. But this statement has another meaning, and follows a long line of proverbs that the life of one is the life of all, and the death of one like the death of all.

In the end, Deckard and his daughter meet, as K accepts his death outside in falling snow in a manner reminiscent of the "Tears in Rain" scene, having succeeded in his mission.

THEMES ON THE BODY:

The movie is centered squarely on the ability to produce a child. This ability is held up as a sacred thing, both by the replicants in what is really a religious sense, as well as by Niander, in a no less religious way, but darkly so.

While the humans are shown to commodify sex and women in general (there are many nude women, but no men in the advertisements), the replicants cherish the ability Rachel has demonstrated to create life, something she did under the protection of her loving partner. The leader of the replicant revolutionaries remarks to this effect that it is true that the replicants have become "more human than human". This seems to certainly be true with regard to the "facts of life".

Parallel to this is the desire of Joi to have a real body, and to be able to have communion with K through a body. As humans, this is a basic and natural desire, and the both replicants and artificial assistants alike crave this solidity. Not only does this apply to sexuality, but even the way in which Joi allows herself to become vulnerable to her form of death by becoming bound to the emanator. To have a body is to be limited, and she gives this gift to K in the manner she is able.

There is a definite sense of sacramentality in the movie, which some value, and which others attempt to objectify and market. The importance of even the mundane, like the wooden horse, serve to show the power of little things and little moments to provide windows into greater meaning.

Much could be written about the economic justice lessons of the movie, but it is enough to point out that children do not seem to be well-received and given a place in the human society.

One additional concept, that of original (or in this case, penultimate) solitude, can be seen in K's encounter with an advertisement for the Joi products after his return to LA, in which he is told, a bit too correctly, that he looks lonely. The inherent fear that comes with this loneliness, and the shame that comes with nakedness in this fallen world is exhibited in the scene where Niander inspects his latest replicant model as she attempts to cover and protect herself. In the world of Blade Runner 2049, it seems this fear is well-justified.

Finally, the movie presents a dystopia which, while not completely to be attributed to the replicant technology, shows a clear link between the ability to produce a person like a commodity and the tendency to treat all persons like commodities thereafter. We would do well to leave such possibilities fictional.

--

--

--

--

--

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/9336723/blade_runner_2049_holo.jpg)